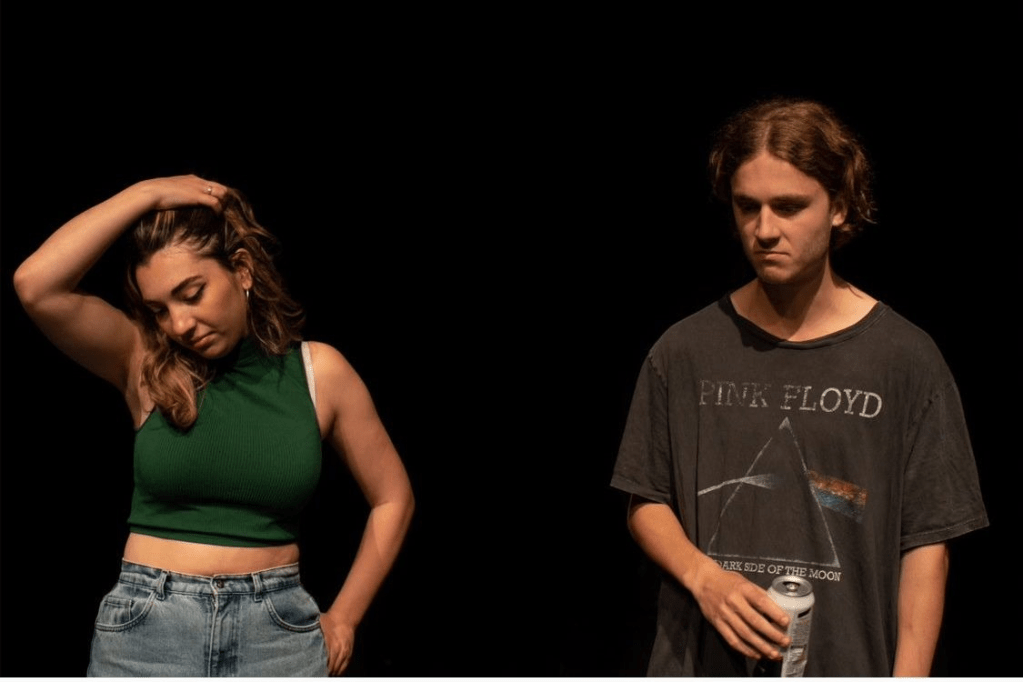

Austin Keane, Year 3

Photo Credit: Saffy Wehren & Abby Swain

In 1987, Fran Lebowitz wrote about the impact of AIDS on the artistic community and her most affecting and oft forgotten point was this—if an audience doesn’t understand the impact of removing queer people from culture then we must consider the fact that soon everyone who does understand what that means will be dead. What remains then is double fold in its creative demand—both legacy and resurrection. With the ‘Open Theatre’s’ Solomon and Atlanta I might argue both have been achieved.

Written by Harry Daisley and directed alongside Izzy Bates, ‘Solomon and Atlanta’ is a carefully crafted story of love set during the AIDS crisis, and told across a decade. Not so much an anatomy of desire as the anatomy of memory, conjuring itself again and again, demanding to be told. The set marks itself as one of quality thanks to Saffy Wehren and Phoebe Sanders, charming the audience before a single word is spoken onstage. Red letters hang from the ceiling, prickling the skylight. Already, for the men in this story, their words watch them—calling to mind Chris Kraus’s maxim: every letter is a love letter—they twist as we breathe. The picture frames are empty, the letters pressed neatly shut; histories lie unrecorded or just unobserved. We, the viewer, have the sense that that is about to change. In the background there is an audio track looping the humming of voices—I’ll be your mirror made of light… This must be the endless summer—lyrics reminiscent of The Velvet Underground and Sufjan Stevens. It is a bold way to set the tone, an unembarrassed commitment to self-seriousness, and one this production proves itself equal to.

The cast were uniformly brilliant. Matt Dangerfield as Atlanta balanced perfectly a sort of lightness conscious of its own overgrown size, becoming heavy in the altered body. In his brilliant laughter we soon begin to understand a fear of time, and memory’s error. Even still, the core of Dangerfield’s skill as a lead lies in his restraint. I could feel his energy, at once crackling in the air—then sublimate to sift vividly beneath his skin, giving a powerful sense of inertia to the quieter scenes. Sharing in this dance is Maddy Swindells, her obvious comfort as Atlanta’s confidante so convincing that it’s painful to witness. She shows a clear versatility between her two roles as Tracy and Betty, switching from the anticipation of tenderness to disillusionment with glittering ease; that her face can conform so easily to a quiet rictus of marital despair without seeming ridiculous is the best and most obvious example of this.

Leading us through this memory is Evan Harris, the storyteller. Their gleeful narration buoys us comfortably across time, managing to convey a dignity earned by that same journey. As a narrative vehicle this is useful; as a character on stage they are singularly powerful. To have the discordant voices of Harris and Dangerfield ring out together is deeply moving: words are spoken over and over; love is re-enacted. (There are always two voices in us, after all.) In a memory, Daisley reminds us, everything begins and ends with the same breath.

The play is well over half gone before Morgan King makes their appearance as the eponymous Solomon. They are slow and awkward, nodding as if by reflex but also in disbelief at Atlanta’s presence. King manages to play a conflicted man without giving an uneven performance—Solomon is altered, made foreign by time, but is not completely without that fragment of beauty that Atlanta remembers. He has nursed it all these years. I was worried that Solomon would appear to us as perfect, a paradigm of male beauty and achillean desire—and therefore bloodless, unlovely—but King circumvents this with tenderness.

At this point Solomon is insufficient and necessarily so: we are allowed to see the single remaining shard that Atlanta can—and mourn it. Their love has already been well characterised. This depiction is helped by an incredibly effective use of staging with a screen and projector-lighting. Here intimacy does not surrender itself to the screen but is emboldened by it. Their desire, the action of it, is definite, obvious, yet obscured. The audience cannot look behind the screen any more than the lovers could have chosen to exist beyond it. It’s a clever trick to offer us further perspective that’s visually stunning as well.

I did note that as the play progresses, the pacing becomes less even. Initially, scenes are brimming with feeling, exploring characters in a domesticity that is both convincing and engaging. But this fades as Atlanta makes his journey to see Solomon, setting their encounter as the single moment of tension. That this meeting is in actuality so brief, having been made so necessary, causes there to be a slight disconnect between the character’s experiences and the audience’s emotional perception of them. The other difficulty was with the use of Evan’s onstage presence. What is a cunning tool is at times over utilised. Atlanta’s feeling is translated so instantaneously that we barely have time to perceive it: Dangerfield is so immediately understood by the audience through this communication that at times we cannot read him at all, only form our impressions over him, rather than let him conduct them to us.

For me going in, the main challenge this production had was that if the audience is expected to believe that Solomon and Atlanta have lost something, we need to be convinced of them having found it in the first place—and this was done undeniably well, especially considering the play’s running time. Still, as I’ve mentioned, you never really touch Solomon—though neither can Atlanta. Thankfully we are not patronised—or worse, bored—with an exploration of Solomon’s religious guilt. Avoiding the pedagogy that too often creeps into narratives that speak to injustice firmly establishes the plays consciousness as a commitment to story and to character, as opposed to being a longform educational leaflet. It’s this, as with many things, that Daisley gets right. (I will ignore the fact that green remains my favourite colour.)

*

Lebovitz understood that if artists disappear, so does their art, and the spirit in which that art can be created and celebrated. Here then is a group of people who have summoned that same spirit back into existence—you can feel their dedication to the story, evident in every colour and sequence—and so demand that it is once again witnessed. It was a pleasure to watch, and to consider.

We cannot rectify a history such as this–that would be to overwrite it. We should not. But when a group of people call us to remember its passing, and make us witness once more its form in decline—this story of the death of a culture—we are left with more than a funeral rite. The audience stir in the final sequence with a clear directive: to fill a frame with its picture; to remember the hidden screen, and where it still stands today, and why; to rend open the scarlet letter…

and even to write one.

Yorkshire MESMAC is advertised alongside this production. They are one of the oldest and largest sexual health organisations in the country, offering services to various communities across Yorkshire, including men who have sex with men, people of colour and other marginalised races, people misusing drugs, sex workers and LGBT+ young people and adults. You can find out more from them or access their services here: https://www.mesmac.co.uk/about-us/who-we-are

References

Lebowitz, F. 1987. THE IMPACT OF AIDS ON THE ARTISTIC COMMUNITY. The New York Times [Online]. [27/11/22]. Available from: https://www.nytimes.com/1987/09/13/arts/the-impact-of-aids-on-the-artistic-community.html