By Austin Keane. Year 3.

Images owned by LS6 Theatre.

Rating: ★★★★☆

“Are you a good person?” This is just one of the things writer and director Rebecca Harrison wants us to consider in her new play–a question that is as much a calling card for a certain audience as it is an actual plea for information. With dialogue sharp enough to cut a portrait–and acting convincing enough to threaten to disassemble it only a few breaths later–this production holds up a brilliant mirror to student life.

The title itself is a construction, an inversion. Like much of the show, things accrue meaning in their relationship to one another, in the patterns that wash over normal life, so that certain words may glimmer–if only under a certain light. All the action occurs in the smoking area of the eponymous bar ‘The Elbow,’ a favourite of our four friends, as they attempt to parse the things that bind them together: rent for a house they have all, at one point, lived in; love, or lack thereof; failing to clean the kitchen properly. The scenes themselves are these ‘asides,’ further punctuated by miscellaneous audio that gives us glimpses of other lives happening alongside the characters. At the same time, ‘to elbow aside’ is an idiom meaning to get past someone and take their place or to literally push someone away, an idea that is closely examined in the play’s main dilemma. Importantly, the narrative is always just off-centre from the pub. It’s a powerful frame to read lives with–to capture a person in motion, perpetually between drinks, always coming or going–but is subtly effective in rendering accurately the liminal spaces young people occupy.

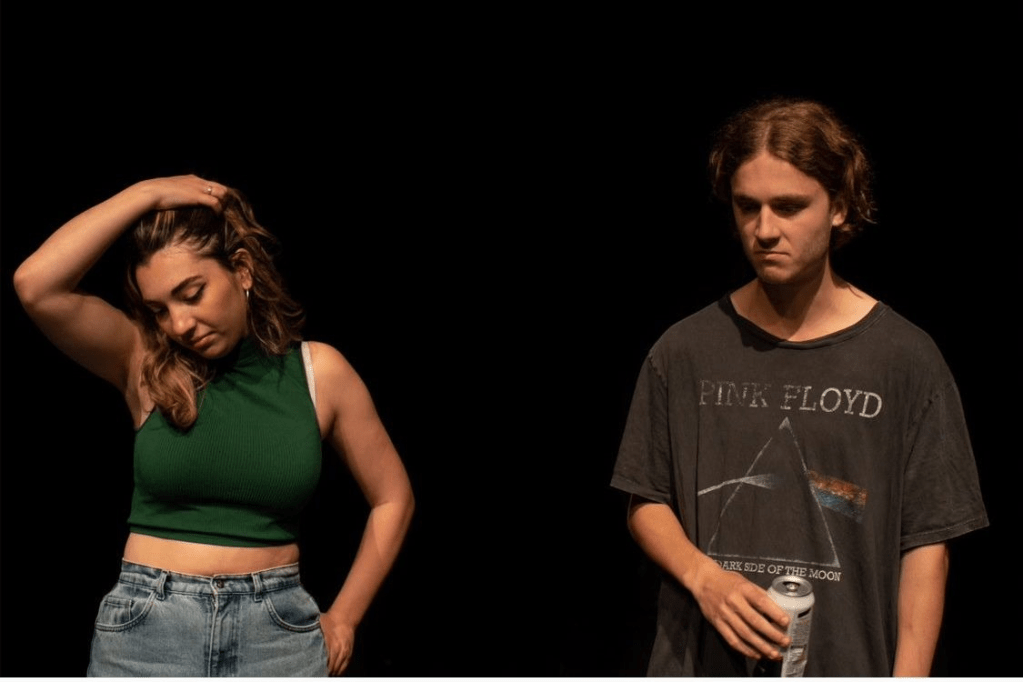

The stage itself was comfortably sparse: an old-style dustbin, a single bench–giving the actors plenty of space to work with, each of them commanding it with a confident and unique attention. The characters are a glorious band of familiar types. There are brothers Sam (Charlie Crozier) and Chris (Matty Edgar), recently estranged after the latter mysteriously disappeared and the former took his place in the house. Crozier embodies the strained stubbornness of the average joe easily, challenging Chris’s elusive sulkiness with the perfect amount of sibling disdain. This tension is shared well between them, held tight enough to make the audience nervous without descending into pantomime. Edgar is persuasive in his delineation of the failed musician, smothered with embarrassment, managing to be surly enough to irritate his friends into argument but not quite the audience.

Joy (Lucy Yellow) and Perry (Carrie Clarke) are close friends and Sam’s roommates. We watch their dynamic play out, dominated at first by Joy’s sour imagination that is then put to the test. For Joy speech all speech is thronged with anger–as if she’s deriving meaning from her language the moment she produces it. Perry is excellent in response, and the perfect antidote to Joy’s ironic bitterness. Clarke proves herself the most versatile, conjuring bizarre monologues with an utter seriousness that’s as affecting as it is hilarious, while managing still to capture tenderness between the laughter. Her wide-eyed fervour appears, as the play progresses, just as much armour as it is artifice. (In response to her boyfriend cheating on her she remembers aloud how he had just said that he loved her; and, in the breath that she thinks about what it means to have two women beholden to you, shouts, ”Don’t you know there’s a recession James?”)

There’s always a turned hand, a flashing eye–ideas, both serious and then deadly funny, threaten to take root there, between them, in the hot air of the room. The intimacy the actors conjure together further aids a trick of perception–that we, the audience, really are among them in the space; that after a drink or two it would be possible to watch these very scenes unfold, unobserved. Here, artefacts of student life are sacrosanct: a borrowed lighter, that silly shuffle from the smoking area, bumping awkwardly into that old friend at the local. Everything glimmers with power–in the ritual of it repeated a thousand times outside the room, remembered and recorded each time they are acted out. And you find as you watch that it’s an utter pleasure to see them pay tribute to real life in this way.

The most stunning moment of the show for me was when Perry, in a therapeutic act, shouts at Sam and Joy pretending they are two people who have recently wronged her, making them co-conspirators. Here, the characters overlay each other in a double exposure, painful for the way in which it reveals rather than obscures them. Like those images plucked straight from normal lives, significance comes from the act being a shared one. There’s some sleight of hand here too, since although Perry does much of the obvious comedy for the show she is not in fact a joke. Perry ends up living the thing Joy is afraid of–and beyond it. She complicates the story in refusing to conform to it. Again and again, we watch the cast spin off of each other with startling ease, living out real fears–in love, in life, above all in belonging–with genuine skill.

I will say that, at times, the dialogue came a little too formed from the lips of the cast; its tenderness was lost in its efficiency. Similarly, the emotion expressed by the cast was at times unbalanced: Sam’s character is limited in his range of expression as his very struggle to communicate what he wants is undermined by how long he remains unmoved for–much of the play–and how relentless this characterisation is. Because of this, language that should glitter disappears the moment it is uttered, making him unfairly less compelling than the others. Even still, the production team of assistant director Ellie Mullins, producer Meg Ferguson and marketing producer Olivia Taylor-Goy, have conjured a moving study in the small but essential moments, powerful for its devotion to people acting out the quotidian tensions that occupy us all. We witness here a brilliant game of asking: the way we ask ourselves what matters, and without knowing demand it of each other.

In watching this excellent production unravel, I realised I had stumbled across another inversion. The question is not ‘are you a good person?’ but ‘are people good’–and that final condition–’to each other.’ Not an individual exercise but a collective one, mirrored and repeated like all these small acts the show pays wonderful attention to. And, just like real life, there is no answer given to us by the end of the play. But with as stunning a portrait of infuriating, silly, entitled, confusing, glorious student life as this, you leave remembering exactly what it is that’s important–that we keep asking it.

‘Asides from the Elbow’ is showing at the Edinburgh Fringe Festival (Perth Theatre) from the 5th to the 14th of August–get your tickets here: https://tickets.edfringe.com/whats-on/asides-from-the-elbow