Lucy Longbottom, Intercalating Medical Student

Every medical student is familiar with the statistic: 1 in 25 people are carriers for cystic fibrosis (Cystic Fibrosis Trust, 2025). Many are also aware of the F508 deletion mutation commonly responsible for this disorder, which often flashes up in pre-clinical lectures. But, despite memorising the basics for exams, there is little further exploration into exactly how this disease manifests on a genetic and molecular level. Where is the affected gene located? How do mutations affect the protein’s ability to function normally? And how does this result in the clinical phenotype we see in cystic fibrosis patients?

Gene locus, and normal protein structure and function

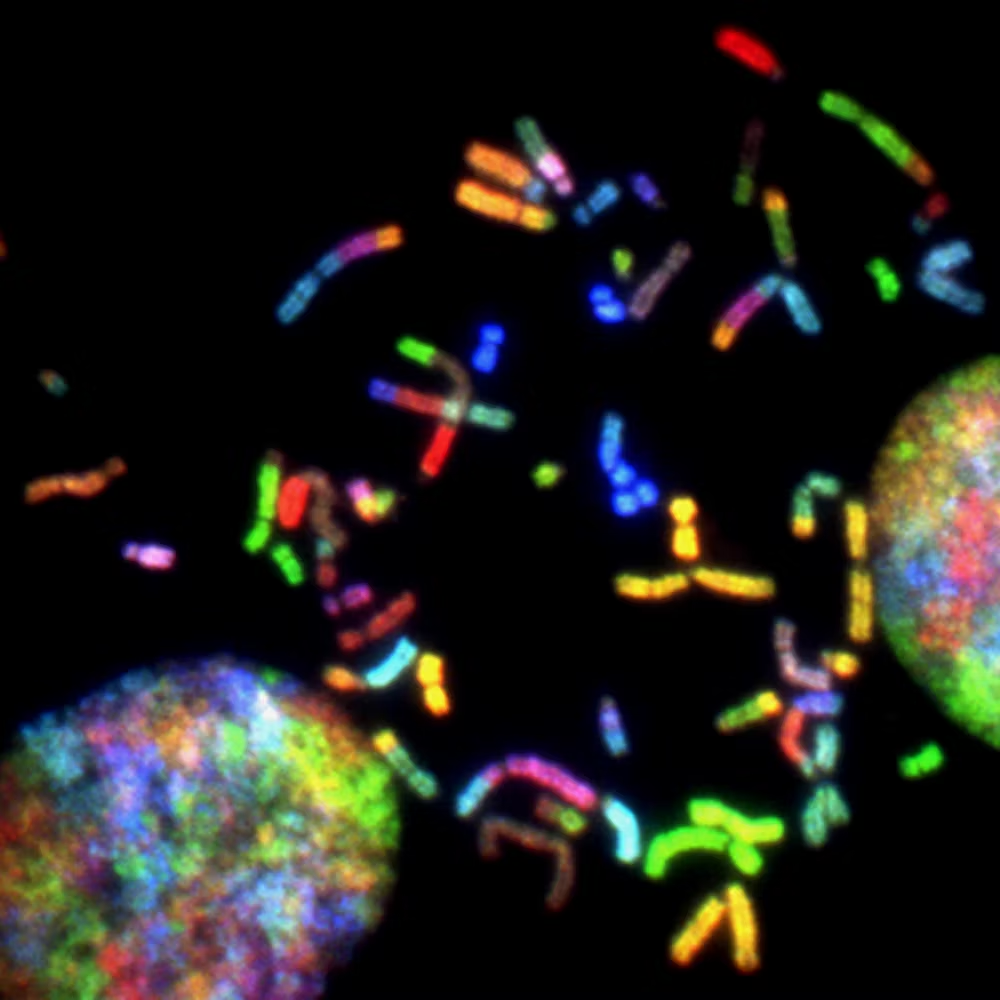

Cystic fibrosis is an autosomal recessive inherited disorder characterised by mutations of the Cystic Fibrosis Transmembrane Conductance Regulator (CFTR) gene (Johns Hopkins University, 1966-2025). The CFTR gene is located on chromosome seven, specifically at position 7q31.2 (Johns Hopkins University, 1966-2025), and is approximately 6,500 nucleotides in length with 24 coding exons (Riordan et al., 1989).

The translated CFTR protein is a type of ATP Binding Cassette (ABC) transporter (Vergani et al., 2005), a superfamily of proteins which broadly function as membrane transporters, powered by ATP hydrolysis (Rees et al., 2009). ABC transporters generally possess four domains: two transmembrane domains (TMDs), spanning the cell’s lipid bilayer, and two nucleotide binding domains (NBDs), within the cell’s cytoplasm (Rees et al., 2009). ATP binds to the NBDs which induces their closure and causes flipping of the TMDs from an inward to outward facing state. Importers can then accept substrates from binding proteins, and exporters can expel substrates extracellularly (Fig. 1). Hydrolysis of ATP reverses this flipping, returning the transporter to an inward facing state (Hollenstein et al., 2007).

Figure 1: Representation of an ABC importer, where nucleotide binding domains (NBDs) and transmembrane domains (TMDs) interact with ATP to translocate substrates across a membrane, adapted from Rees et al., 2009

The specific protein structure of CFTR is much in concordance with this general structure, consisting of two NBDs and two membrane spanning domains (MSDs). These MSDs are equivalent to the TMDs mentioned above as they span the cell’s membrane, but this different name is used when referencing CFTR’s structure specifically, so I will use ‘MSD’ from here. In addition to these, CFTR has a unique regulatory ‘R’ domain (Serohijos et al., 2008). Cytoplasmic loops (regions of the MSDs) facilitate the formation of interfaces between NBDs and MSDs, enabling synthesis of a stable tertiary structure (Fig. 2). A notable amino acid, phenylalanine, at position 508 (Phe-508), is located in NBD1 and mediates its interface with MSD2 by forming crosslinks with cysteines at cytoplasmic loop 4, resulting in the cross-linking of the two domains (Serohijos et al., 2008). As for the R domain, its role involves regulation of channel gating, whereby the phosphorylation of the R domain by protein kinases, in combination with ATP binding and hydrolysis at NBDs, is required for CFTR normal channel functioning (He et al., 2008).

Figure 2: Schema of CFTR structure (A) and corresponding 3D model of CFTR protein (B), depicting the specific interfaces that form between cytoplasmic loop four (CL4) on membrane spanning domain two (MSD2) and nucleotide binding domain one (NBD1), and cytoplasmic loop two (CL2) on membrane spanning domain one (MSD1) and nucleotide binding domain two (NBD2). Adapted from Serohijos et al. (2008).

Functionally, the CFTR protein is an anion channel (Kartner et al., 1991) – the only known ion transporter within the ABC family (Riordan, 2008) – involved in transepithelial chloride ion transport at the apical membrane (Anderson et al., 1991). Consequentially, CFTR plays a crucial role in fluid and electrolyte homeostasis in many exocrine tissues (Sheppard and Welsh, 1999; Riordan, 2008).

CFTR mutations

Over 2000 CFTR variants have been identified worldwide and, of a sample of 1,167 variants, ~70% were pathological for cystic fibrosis (Johns Hopkins University, 2024). The majority are missense mutations (The Hospital for Sick Children (SickKids), 2011; Bell et al., 2015) whereby a codon alteration leads to the translation of a different amino acid at that position. The most common pathological CFTR mutation is ‘F508del’ – the deletion of Phe-508 – with ~90% of the cystic fibrosis population carrying the mutation in at least one allele, and 50% of those homozygous for the mutation (Boyle and De Boeck, 2013).

The F508del mutation is a codon deletion causing absence of Phe-508 at NBD1, reducing the strength of its interface with MSD2 and its interaction with NBD2 (McDonald et al., 2022). The resulting protein is misfolded and ultimately degraded by ubiquitin ligases at the endoplasmic reticulum (Riepe et al., 2024), meaning a functional CFTR protein fails to reach the apical membrane.

CFTR mutations can be split into six classes (Fig. 2) (Boyle and De Boeck, 2013). Crucially, regardless of mutation class or type, all mutations pathological for cystic fibrosis result in loss of function of the CFTR protein. Broadly, class one and two mutations result in the absence of a functional CFTR protein at the epithelial apical membrane, class three and four mutations result in defective channel functioning at the apical membrane, and class five and six involve reduced synthesis or stability of the CFTR protein (Boyle and De Boeck, 2013). Class two is the most common, under which F508del falls (Boyle and De Boeck, 2013).

Figure 3: CFTR mutation classes, from Boyle and De Boeck, 2013.

Clinical manifestations and therapeutics

Clinically, the dysfunctional chloride transport and fluid regulation in cystic fibrosis results in production of dehydrated, viscous secretions at exocrine surfaces, leading to obstruction, inflammation, and eventual tissue damage and impaired organ functioning (Riordan, 2008; Cutting, 2015). Key organ systems affected include the lungs, where obstructive pulmonary disease develops due to the formation of inflammatory mucus plugs and plaques (Turcios, 2020); and the pancreas, where obstruction of the ductal canal and resultant exocrine tissue loss can cause pancreatic insufficiency (Coderre et al., 2021). Additional affected tissues include the liver and bile ducts (Leung and Narkewicz, 2017), the sweat glands (causing the characteristically elevated sweat chloride concentration) (Cutting, 2015), and the male reproductive tract, where infertility from congenital bilateral absence of the vas deferens occurs in 95% of cystic fibrosis males (de Souza et al., 2018).

Whilst there is no cure for the disorder, pharmacological agents, called CFTR modulators (Taylor-Cousar et al., 2023), have been developed that can target the proteins’ functional deficits caused by specific mutations. Ivacaftor, a CFTR potentiator, increases channel opening probability as well as chloride secretion of CFTR in cells with class three mutations (such as Gly551Asp) (Van Goor et al., 2009). Due to the nature of class two mutations, CFTR correctors such as Lumacaftor were then developed to increase CFTR trafficking to the apical membrane in F508del homozygotes and improve chloride secretion (Van Goor et al., 2011). Clinically, Ivacaftor can be used in combination with a CFTR corrector to maximise CFTR functioning in F508del variants (NICE, 2017; Taylor-Cousar et al., 2023).

Evidently, comprehensive knowledge of how mutations in the CFTR gene affect the translated proteins’ structure and function is vital to clinicians’ understanding of the disease, and the development of therapies which attempt to target and correct this loss of function. Through continued research, we can only hope to expand upon the knowledge gained over the past few decades and develop novel interventions which serve to improve the quality of life for those living with cystic fibrosis.

References

Anderson, M.P., Gregory, R.J., Thompson, S., Souza, D.W., Paul, S., Mulligan, R.C., Smith, A.E. and Welsh, M.J. 1991. Demonstration That CFTR Is a Chloride Channel by Alteration of Its Anion Selectivity. Science. 253(5016), pp.202-205.

Bell, S.C., De Boeck, K. and Amaral, M.D. 2015. New pharmacological approaches for cystic fibrosis: Promises, progress, pitfalls. Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 145, pp.19-34.

Boyle, M.P. and De Boeck, K. 2013. A new era in the treatment of cystic fibrosis: correction of the underlying CFTR defect. The Lancet Respiratory Medicine. 1(2), pp.158-163.

Coderre, L., Debieche, L., Plourde, J., Rabasa-Lhoret, R. and Lesage, S. 2021. The Potential Causes of Cystic Fibrosis-Related Diabetes. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 12, p702823.

Cutting, G.R. 2015. Cystic fibrosis genetics: from molecular understanding to clinical application. Nat Rev Genet. 16(1), pp.45-56.

Cystic Fibrosis Trust. 2025. Information for carriers. [Online]. [Accessed 12 January]. Available from: https://www.cysticfibrosis.org.uk/what-is-cystic-fibrosis/diagnosis/information-for-carriers

de Souza, D.A.S., Faucz, F.R., Pereira-Ferrari, L., Sotomaior, V.S. and Raskin, S. 2018. Congenital bilateral absence of the vas deferens as an atypical form of cystic fibrosis: reproductive implications and genetic counseling. Andrology. 6(1), pp.127-135.

He, L., Aleksandrov, A.A., Serohijos, A.W., Hegedus, T., Aleksandrov, L.A., Cui, L., Dokholyan, N.V. and Riordan, J.R. 2008. Multiple membrane-cytoplasmic domain contacts in the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) mediate regulation of channel gating. J Biol Chem. 283(39), pp.26383-26390.

Hollenstein, K., Dawson, R.J.P. and Locher, K.P. 2007. Structure and mechanism of ABC transporter proteins. Current Opinion in Structural Biology. 17(4), pp.412-418.

Johns Hopkins University. 1966-2025. CYSTIC FIBROSIS TRANSMEMBRANE CONDUCTANCE REGULATOR; CFTR. [Online]. [Accessed 8 January]. Available from: https://www.omim.org/entry/602421

Johns Hopkins University. 2024. The Clinical and Functional TRanslation of CFTR (CFTR2). [Online]. [Accessed 10 January]. Available from: http://cftr2.org

Leung, D.H. and Narkewicz, M.R. 2017. Cystic Fibrosis-related cirrhosis. Journal of Cystic Fibrosis. 16, pp.S50-S61.

NICE. 2017. Cystic fibrosis: diagnosis and management. [Online]. [Accessed 12 January]. Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng78

Rees, D.C., Johnson, E. and Lewinson, O. 2009. ABC transporters: the power to change. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology. 10(3), pp.218-227.

Riordan, J.R. 2008. CFTR Function and Prospects for Therapy. Annual Review of Biochemistry. 77(Volume 77, 2008), pp.701-726.

Riordan, J.R., Rommens, J.M., Kerem, B., Alon, N., Rozmahel, R., Grzelczak, Z., Zielenski, J., Lok, S., Plavsic, N., Chou, J.L. and et al. 1989. Identification of the cystic fibrosis gene: cloning and characterization of complementary DNA. Science. 245(4922), pp.1066-1073.

Serohijos, A.W., Hegedus, T., Aleksandrov, A.A., He, L., Cui, L., Dokholyan, N.V. and Riordan, J.R. 2008. Phenylalanine-508 mediates a cytoplasmic-membrane domain contact in the CFTR 3D structure crucial to assembly and channel function. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 105(9), pp.3256-3261.

Sheppard, D.N. and Welsh, M.J. 1999. Structure and Function of the CFTR Chloride Channel. Physiological Reviews. 79(1), pp.S23-S45.

Taylor-Cousar, J.L., Robinson, P.D., Shteinberg, M. and Downey, D.G. 2023. CFTR modulator therapy: transforming the landscape of clinical care in cystic fibrosis. The Lancet. 402(10408), pp.1171-1184.

The Hospital for Sick Children (SickKids). 2011. Cystic Fibrosis Mutation Database. [Online]. [Accessed 10 January]. Available from: http://www.genet.sickkids.on.ca/

Turcios, N.L. 2020. Cystic Fibrosis Lung Disease: An Overview. Respiratory Care. 65(2), p233.

Van Goor, F., Hadida, S., Grootenhuis, P.D.J., Burton, B., Cao, D., Neuberger, T., Turnbull, A., Singh, A., Joubran, J., Hazlewood, A., Zhou, J., McCartney, J., Arumugam, V., Decker, C., Yang, J., Young, C., Olson, E.R., Wine, J.J., Frizzell, R.A., Ashlock, M. and Negulescu, P. 2009. Rescue of CF airway epithelial cell function in vitro by a CFTR potentiator, VX-770. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 106(44), pp.18825-18830.

Van Goor, F., Hadida, S., Grootenhuis, P.D.J., Burton, B., Stack, J.H., Straley, K.S., Decker, C.J., Miller, M., McCartney, J., Olson, E.R., Wine, J.J., Frizzell, R.A., Ashlock, M. and Negulescu, P.A. 2011. Correction of the F508del-CFTR protein processing defect in vitro by the investigational drug VX-809. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 108(46), pp.18843-18848.

Vergani, P., Lockless, S.W., Nairn, A.C. and Gadsby, D.C. 2005. CFTR channel opening by ATP-driven tight dimerization of its nucleotide-binding domains. Nature. 433(7028), pp.876-880.

Leave a comment