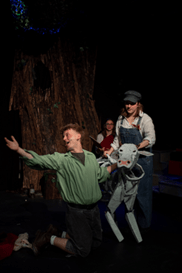

Austin Keane, Year 3. Photography courtesy of Abby Swain.

“Nice… is different than good,” Little Red warns us having escaped the Wolf. We all know one—a production that saunters and jaunts and, after only a little biting, falls dead before the first half. A joy to find then, that this production is both: nice and good.

‘Into The Woods,’ a second-semester show from ‘LUU Musical Theatre Society,’ is a great musical (if not only in the giant sense) and is plagued by not one but two giants. Sondheim’s lexical deftness exists as a brilliant, terrible force of its own throughout the show, present most perhaps in the minds of the performers on stage. However, under Evey Jermy and Erin Gazeley’s direction, this giant already stands as formidable.

Buoyed by a live orchestra that brilliantly performs the score, and with musical and creative direction from Jenna Bowman and Lucy Yellow respectively, the polyphonic narrative remains near weightless, turning on the slightest breath. The efforts of producers Ben Nuttall and Jennie Bodger and production manager Kate Matthews are self-evident: on a beautifully crafted set—a single great tree in the far corner; a sweep of leaves across the ceiling—the story plays out with verve and humour. Green light filters the air; birds tweet out; the strings tun-up. Everyone is having fun.

All this, before we even consider the performances.

*

Precocity, as with many of the affects of childhood, is a brittle thing. That said, Whiteaway’s Little Red invites scrutiny in her performance of childhood—much as children themselves do—and does not break. An audience must pay attention to her, and be quite without embarrassment. Set nicely against the wide-eyed Toby Bowen as Jack—his ‘Giants In The Sky’ touching in its gulping picture of naïveté—they both convey innocence before the fall and manage to capture fully the spirits of their characters. Further, in listening to Little Red we understand that she may wear the Wolf—but is she truly ever to become it? Or, as with the furry thing itself, as the blade glittering in her hand reminds us, it might come straight off. Whiteaway is funny here, but darkly, unconsciously—it is the first warning of what is to come.

The Baker and The Baker’s Wife especially surprised me. To my mind, the dullest of the characters—that is until the second half—they have no small task: to make interesting and novel the construction of a nuclear family. However, the sweet seriousness of ‘It Takes Two’ and the undeniable strength of both performances from Harry Toye and Talia Goss meant that there was a clear freshness and illumination in their conflict. The domestic plot between them is convincing and confidently engaging.

Florinda and Lucinda, played by Cam Griffiths and Bethan Green respectively, work in perfect dyssynchrony to terrorise and amuse. Not a second of time is wasted—screaming and stalking the stage, sweet as rot, both know just how funny their performances are. Held steady by Victoria Norman as the Stepmother, together they have the air of Macbethean witches sans prophetic wisdom. They are dreadful—brilliantly, dreadful.

Ellen Corbett gives a strong performance as Cinderella, navigating (on) the steps of the place with physical and musical deftness. Corbett’s dedication to the performance is especially notable; again, what could otherwise easily be flat, worn thin with the repetition of telling—a girl, a prince, a shoe—hums with energy. Andie Curno gives an energetic performance as the Witch and manages to make the conceit of the play, suspiciously algebraic, more digestible without losing the glitter of the language that communicates it.

Henry Marshall is cast well as the Wolf with his leering manner, both vile and cunning. He makes an appearance again as one of two Princes, the other (belonging to Rapunzel) played by Alex Howe. Thanks to their efforts ‘Agony’ remains as funny as ever; the syncopated movements of Howe and Marshall are perfectly clumsy and inventive. They propel much of the comedy for the first act: one must take himself too seriously; the other is barely able to suspend disbelief at this as a possibility. Between them is conjured a charm that glitters as much as it gutters.

However, It is more difficult to appreciate the emotional relevance they bring to scenes (or are intended to) as the show progresses, through no fault of their own. This is an emotional incongruence that proves more distracting in the second half. You can spy the force of the tale—that immutable construct of the plot—push the Princes, the Baker, and the Witch, faces still ruddy with laughter, confusion, and dread, into quieter contexts, demanding more restraint. However, with a running time that already grazes three hours the need for brevity in between songs is understandable and the effect minor—after all, the show should accelerate, and not much is left behind.

In ‘No One Is Alone’ the emotional element works much better again. Confusion is given a more appropriate space to occupy—here, at least, can exist tenderness. Similarly, Curno’s Witch also benefits from the second act’s emotional intensity. The anger of their performance works much better when worn with pain, and not just the latent memory of it.

Special attention should be brought to two particular performers. The first is the Narrator, played by Jenna Bowman, who thrills with a cool charm. Then quickly, even the sudden spoiling of this ease is made delightful: there is an impressive chill in the room as they attempt to sacrifice the Narrator. The metaphysics of the thing remains light and engaging, surprising even, but not overwrought. The other is Talia Goss, who in ‘Moments In The Woods’ exhibits a display of vocal control and emotion that makes what is challenging appear easy or obvious. This performance confirms Goss as the core of the show’s successful and elegant rendering.

Sweeping performances aside, there remain many small scenes that can stand in isolation. Milky White, beautifully constructed and convincingly skeletal, was brought to life by Amelia Perry. In death, Perry lets the puppet drop and watches it for a moment, deadpan, before relaxing and leaving the stage. Sublime. Then we have Cinderella’s birds, painfully funny and wonderfully conceived; Jack’s mother, played by Emma Wilcox, bridling his youth with stern, slight motions; Ellery Turgoose’s struggle as Granny, and the charming rendering of her escape.

Other gems: Lucy Davey’s warbling as Rapunzel is as beautiful and ridiculous as it should be; the Mysterious Man’s intrusions, courtesy of Matteo Ferrari, stand both jarring and hilarious; Harry Daisley’s Harp, as his head is thrown back in paroxysmal delight at his own fabulousness. All of this is further supported by a variety of detailed costumes, each carefully drawn up by Eva Lafontan. And the Round is used well too: the great rope of Rapunzel’s hair; a bare glimpse of the Wolf stalking the aisle.

Another thing I noticed was the volume of cast members and their movement on stage. The physical force of eighteen voices in unison was employed well and with restraint. Considering this, the use of a Chevron (more than once!) is inevitable—and forgivable. The overall effect was powerful enough to make me consider that if the audience was allowed to break into song—they would!

*

Ultimately, the characters are instructed into reflection: to stop wishing and wanting alone, and to question whether their story is important. All change is attended with the thrill of suffering—and they have suffered terribly, all. It’s a big ask of the audience, but in the end, we’re glad that we’re uncomfortable, that we don’t exactly like them; that we might pity the giants, tall and terrible though they are. Here then is proof, that in capable hands giants can stay great, as well as troubling, can be not just big and terrible but

—“Awesome, scary / Wonderful giants in the sky!

Leave a comment