Understanding the complex relationship between Multiple Sclerosis and Epstein Barr Virus

Rishabh Suvarna, Year 1

The nervous system is one of the most complex systems in the human body, but in order to function as efficiently as it does, it relies on a tightly bound network of connective tissue called the neuroglia, comprising at least 50% of the brain tissue (Verkhratsky et al., 2019). One of these neuroglial cells are the microglia, acting as the brain’s own innate immune defence cells, attacking pathogens that have managed to infiltrate the blood brain barrier (Purves et al., 2001). However, when these neuroglial cells are compromised, this can lead to a plethora of problems. One of them is Multiple Sclerosis, promoting neuroinflammation, oligodendrocyte apoptosis (i.e. programmed cell death of other neuroglia) and demyelination. This occurs as they present antigens through MHC (Major Histocompatibility Complex) I/II, to Th1 and Th17 lymphocytes circulating the brain, all of which have been extensively investigated in fibrous lesions caused by Multiple Sclerosis (Luo et al., 2017).

Multiple Sclerosis (MS) is a neurodegenerative disease affecting the central nervous system, involving an autoimmune attack mediated by phagocytic microglial cells on the axons of nerves, permanently scarring the myelin sheath of numerous neurons. It is the leading cause of non-traumatic disability in young adults, with symptoms first presenting at ages 20-40. This leads to progressive neuronal dysfunction, causing neurological deficits in the autonomic and sensorimotor divisions of the nervous system and thus leading to problems with sight, muscle-coordination, balance, speech and cognitive function (Ghasemi et al., 2017). This is summarised by Figure I.

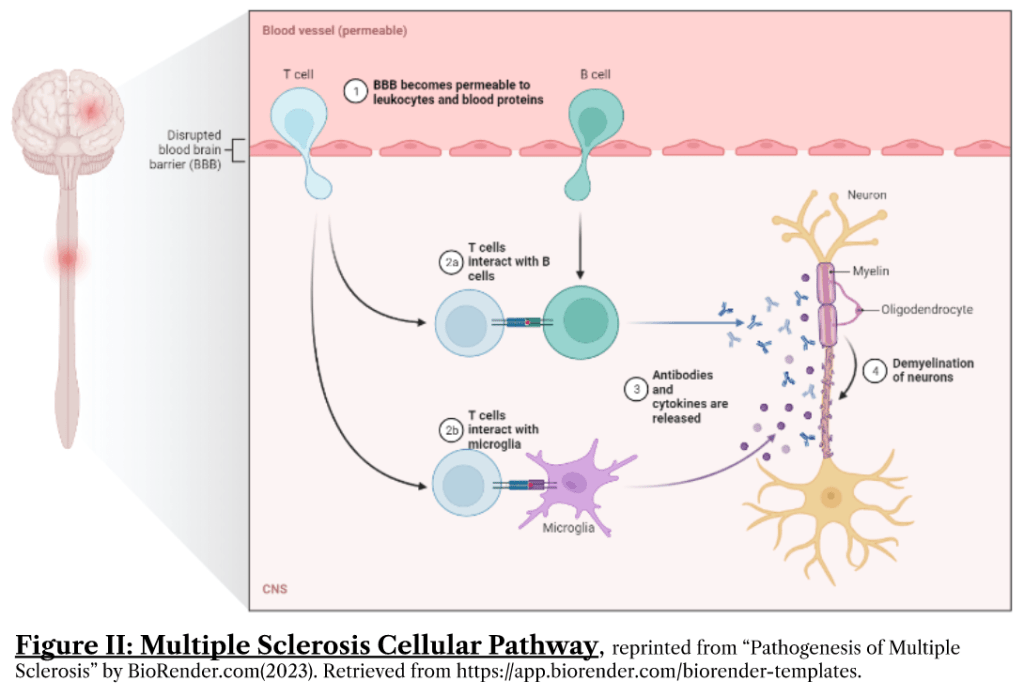

The release of chemical messengers such as cytokines (e.g. Interleukin-1, Interleukin-6, TNF-α), nitrous oxide and other reactive oxidative species (ROS) results in oligodendrocyte death, and astrogliosis (hyper-proliferation of astrocytes in an effort to isolate axonal damage) that halts remyelination and results in irreversible glial scars commonly seen in MS patients (Correale and Farez, 2015). Consequently, permanent demyelination occurs as axons lose their fatty myelin sheath that provides electrical insulation from the external environment and thus means electrical signals travel much more slowly, seen in Figure II.

MS is known to affect females more than males, common in most autoimmune conditions (Harbo et al., 2013). Apart from this, it is also known that low vitamin D levels, trauma, smoking, obesity, early adulthood and mononucleosis (otherwise known as “glandular fever”, caused by Epstein Barr Virus) are strongly associated with development of MS (Reich et al., 2018).

Despite this, scientists have not been able to pinpoint specific environmental/genetic causes. This was the case until very recently, where epidemiological analysis may have just lead to another breakthrough in the field of clinical neuroscience, being the causative link between Epstein Barr Virus (EBV) infection and MS development that was established by Dr Kjetil Bjornevik and his colleagues at the department of Public Health in Harvard University.

Before proceeding, we first need to understand what was already known about the pathophysiology of EBV infections. EBV infection is acquired before ages 5-8 in LEDCs but is delayed till adolescence/adulthood in MEDCs. Primary infection before 5 years is mostly asymptomatic, with only those acquiring it in adolescence developing infectious mononucleosis. EBV triggers mononucleosis or glandular fever by infiltrating lymphocytes, resulting in an atypical, hyper-production of CD8+ T lymphocytes and Natural Killer (NK) cells, causing them to appear more like monocytes instead of typical lymphocytes (hence the name).

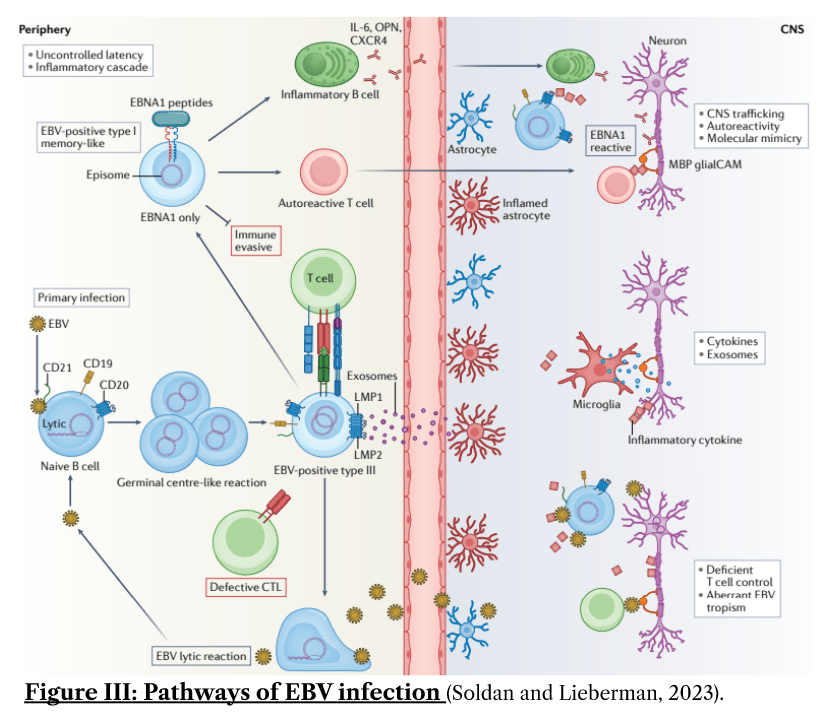

The molecular pathway of mononucleosis is as follows: EBV particles enter squamous epithelial cells lining the airway, reproducing within them using the cell’s internal machinery and then crossing the mucosal epithelial barrier via transcytosis to infect local infiltrating B lymphocytes through gp350 and CD21 proteins found on its surface. Following this, they are shown to reprogramme germinal centres, occurring through a multitude of mechanisms, some of which include: inhibition of MHC Class II synthesis and interleukin-2 (IL-2), Interferon Gamma (IFN-γ) which are needed for CD4+ Helper T activation. It also upregulates TNF, lymphotoxin-α, PDL1 thereby disrupting both innate and adaptive immune responses oncogenically. These pathways are summarised by Figure III (Soldan and Lieberman, 2023).

The net effect of this is that it impairs the maturation process of B lymphocytes, allowing for numerous B lymphocytes to be produced and thus functioning as reservoirs for EBV copies, with the capability to reactivate in the oropharynx (Thompson and Kurzrock, 2004) and occasionally in the meninges of the brain (Hassani et al., 2018), leading to neurodegenerative disease.

Structural studies have also suggested MS development to occur via molecular mimicry, whereby components of the neuron possess structurally similar epitopes (parts of the antigen that bind to antibodies) to that produced as a response to infection, leading to autoimmune responses in the brain. Lang’s work highlighted the structural similarities that are present between EBV peptides and Myelin Basic Protein (Lang et al., 2002), an intrinsically disordered protein that constitutes approximately 30% of total CNS myelin and is a common CSF marker used in supporting neurodegenerative diagnoses including MS (Martinsen and Kursula, 2022). Crystallography revealed that the conformation of MHC parts in the TCR-α region was highly conserved, with the same TCR-peptide contacts. This is believed to exist because this helps to increase the number of epitopes that are available for antigen presentation to a single cross-reactive TCR, improving infection control by allowing for polyclonal antibodies. However, when a specific loci of the MHC class II receptor is expressed (HLA-DR2), this can lead to MS susceptibility and relapses, notably when coinciding with infections of the upper airway (Sibley et al., 1985). Thus, this can possibly lead to activation of autoreactive CD8+ Cytotoxic T lymphocytes, proven via past molecular mimicry studies on mouse models that examine CD8+ dependent autoimmune diseases affecting the heart and eyes (Chandran and Hutt-Fletcher, 2007).

Inspite of the above and the fact that EBV infects 90% of adults worldwide (Wong et al., 2022), only a small proportion of the infected population later develop MS as most EBV infections are not disease-causing, so understanding cofactors and aberrations in the normal infection process is vital to treatment/prevention of MS. In addition, the virus is not always found in MS lesions (Peferoen et al., 2010), so identification of MS genotypes and cofactors associated with EBV is all the more challenging.

However, this might have all been changed by the Harvard neuroscientists. Published in Science in January 2022, the longitudinal study featured seroepidemiological data from active, racially-diverse US military recruits across the past 2 decades with 955 recruits developing MS (Bjornevik et al., 2022). This was identified by making use of the blood samples that were routinely collected by the US Department of Defense Serum Repository (DoDSR) for HIV testing. Using these samples, they were then tested for the presence of antibodies for EBV peptides, as a marker of EBV infection and these were then matched on every characteristic (age, sex, race, ethnicity, branch of military service and collection of blood sample dates) against 2 randomly selected participants without MS, ensuring that everyone was still alive and actively carrying out military service during diagnosis to avoid confounding factors. The risk of MS was found to increase 32 fold if infected by EBV only and not viruses with similar mechanisms of infiltration such as Cytomegalovirus, with MS symptoms appearing after a median time of 7.5 years between the last seronegative sample and first seropositive sample.

This discovery was made by illustrating that EBV seroconversion (i.e. the process of producing specific antibodies against EBV) increased serum levels of neurofilament light chain (NFL), a neuron-specific cytoskeletal protein often used as a sensitive diagnostic marker for MS (Ning and Wang, 2022). It is a structural scaffolding protein that is needed to promote radial growth, stability and maintain the diameter of the axon during the transmission of action potentials. During axonal damage, excessive neurofilaments flood the cerebrospinal fluid and serum, with more severe levels of MS progression associated with higher serum NFL levels according to Expanded Disability Status Scales (Thebault et al., 2020). The study found that NFL levels increased significantly 6 years prior to onset of MS and post-EBV infection, implying that it might be an accurate biomarker of the time of initiation of MS, which has always been difficult to pinpoint clinically.

Using VirScan for virome-wide screening, the scientists were able to identify a significantly higher anti-EBV antibody response in MS cases, with negligible changes in antibody response to the other 110,000 common viral peptides when comparing between healthy/MS patients, showing that MS development was not merely due to opportunistic viral infections.

In addition, 97% seroconversion was observed in people that developed MS, showing that a substantial amount of people that acquired MS later were EBV positive earlier and this relation seems to be unique. This is because MS risk was surprisingly lower with Cytomegalovirus (CMV) positive than CMV negative patients, which suggests that the immune response to CMV ameliorates the adverse effects of EBV.

All these staggering statistics illustrate that EBV infection precedes MS development, providing strong evidence that it is a likely cause of MS whilst also highlighting techniques that could be standardised for the diagnosis of MS such as serum NFL testing. It also suggests that directly targeting EBV through EBV-specific T-cell therapy may thus be more fruitful than anti-CD20 monoclonal antibodies that are usually prescribed as effective treatment for MS, as it averts the risks of intravenous admission and risks of greater/more severe opportunistic infections with depleted memory B cells as drawbacks of anti-CD20 therapies.

Thus, this highlights the need for rigorous epidemiological and biochemical studies as presented here. By understanding the principal factors of the inflammation leading to irreversible MS, we are better able to identify key therapeutic targets for MS patients and enhance their quality of life through more successful treatment plans.

References

Bjornevik, K., Cortese, M., Healy, B.C., Kuhle, J., Mina, M.J., Leng, Y., Elledge, S.J., Niebuhr, D.W., Scher, A.I., Munger, K.L. and Ascherio, A. 2022. Longitudinal analysis reveals high prevalence of Epstein-Barr virus associated with multiple sclerosis. Science. 375(6578), pp.296–301.

Chandran, B. and Hutt-Fletcher, L. 2007. Gammaherpesviruses entry and early events during infection In: A. Arvin, G. Campadelli-Fiume, E. Mocarski, P. S. Moore, B. Roizman, R. Whitley and K. Yamanishi, eds. Human Herpesviruses: Biology, Therapy, and Immunoprophylaxis [Online]. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Accessed 1 April 2023]. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK47405/.

Correale, J. and Farez, M.F. 2015. The Role of Astrocytes in Multiple Sclerosis Progression. Frontiers in Neurology. 6, p.180.

Ghasemi, N., Razavi, S. and Nikzad, E. 2017. Multiple Sclerosis: Pathogenesis, Symptoms, Diagnoses and Cell-Based Therapy. Cell Journal (Yakhteh). 19(1), pp.1–10.

Harbo, H.F., Gold, R. and Tintoré, M. 2013. Sex and gender issues in multiple sclerosis. Therapeutic Advances in Neurological Disorders. 6(4), pp.237–248.

Hassani, A., Corboy, J.R., Al-Salam, S. and Khan, G. 2018. Epstein-Barr virus is present in the brain of most cases of multiple sclerosis and may engage more than just B cells. PloS One. 13(2), p.e0192109.

Lang, H.L.E., Jacobsen, H., Ikemizu, S., Andersson, C., Harlos, K., Madsen, L., Hjorth, P., Sondergaard, L., Svejgaard, A., Wucherpfennig, K., Stuart, D.I., Bell, J.I., Jones, E.Y. and Fugger, L. 2002. A functional and structural basis for TCR cross-reactivity in multiple sclerosis. Nature Immunology. 3(10), pp.940–943.

Luo, C., Jian, C., Liao, Y., Huang, Q., Wu, Yuejuan, Liu, X., Zou, D. and Wu, Yuan 2017. The role of microglia in multiple sclerosis. Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment. 13, pp.1661–1667.

Martinsen, V. and Kursula, P. 2022. Multiple sclerosis and myelin basic protein: insights into protein disorder and disease. Amino Acids. 54(1), pp.99–109.

Ning, L. and Wang, B. 2022. Neurofilament light chain in blood as a diagnostic and predictive biomarker for multiple sclerosis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLOS ONE. 17(9), p.e0274565.

Peferoen, L.A.N., Lamers, F., Lodder, L.N.R., Gerritsen, W.H., Huitinga, I., Melief, J., Giovannoni, G., Meier, U., Hintzen, R.Q., Verjans, G.M.G.M., Van Nierop, G.P., Vos, W., Peferoen-Baert, R.M.B., Middeldorp, J.M., Van Der Valk, P. and Amor, S. 2010. Epstein Barr virus is not a characteristic feature in the central nervous system in established multiple sclerosis. Brain. 133(5), pp.e137–e137.

Purves, D., Augustine, G.J., Fitzpatrick, D., Katz, L.C., LaMantia, A.-S., McNamara, J.O. and Williams, S.M. 2001. Neuroglial Cells. Neuroscience. 2nd edition.

Reich, D.S., Lucchinetti, C.F. and Calabresi, P.A. 2018. Multiple Sclerosis. The New England journal of medicine. 378(2), pp.169–180.

Sibley, W., Bamford, C. and Clark, K. 1985. CLINICAL VIRAL INFECTIONS AND MULTIPLE SCLEROSIS. The Lancet. 325(8441), pp.1313–1315.

Soldan, S.S. and Lieberman, P.M. 2023. Epstein–Barr virus and multiple sclerosis. Nature Reviews Microbiology. 21(1), pp.51–64.

Thebault, S., Abdoli, M., Fereshtehnejad, S.-M., Tessier, D., Tabard-Cossa, V. and Freedman, M.S. 2020. Serum neurofilament light chain predicts long term clinical outcomes in multiple sclerosis. Scientific Reports. 10(1), p.10381.

Thompson, M.P. and Kurzrock, R. 2004. Epstein-Barr virus and cancer. Clinical Cancer Research: An Official Journal of the American Association for Cancer Research. 10(3), pp.803–821.

Verkhratsky, A., Ho, M.S., Zorec, R. and Parpura, V. 2019. The Concept of Neuroglia. Advances in experimental medicine and biology. 1175, pp.1–13.Wong, Y., Meehan, M.T., Burrows, S.R., Doolan, D.L. and Miles, J.J. 2022. Estimating the global burden of Epstein–Barr virus-related cancers. Journal of Cancer Research and Clinical Oncology. 148(1), pp.31–46.

Leave a comment