The neuroscientists’ latest discovery may provide the SLYM chance needed to reverse the progression of Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s, Multiple Sclerosis and more…

Rishabh Suvarna, Year 1

The brain, with its 80 million neurons, is one of the most fascinating, vital and elusive organs that distinguishes the human species from the rest of the other organisms on the planet. A century ago, intricate cognitive functions like emotion, thought and behaviour were shrouded in mystery, but with more precise instruments and rigorous study designs, significant networks of the brain have been identified, leading to a more comprehensive understanding of the central nervous system (Lisman, 2015). Despite recent advancements in the clinical neurosciences and neuro-imaging techniques, appallingly little is known about how the brain functions down to the microscopic level (Batista-García-Ramó and Fernández-Verdecia, 2018).

On Thursday, 5th January, a recent breakthrough discovery published in Science has unveiled a previously undiscovered layer of neuroanatomy that shields grey matter, regulates cerebrospinal fluid and recruits immune cells to monitor for infection. This poignant finding stems from the brilliant minds at the University of Copenhagen, namely Maiken Nedergaard, co-director for the Center of Translational Neuromedicine and Dr. Kjeld Mollgard, M.D. Their combined genius revolutionised the field of neuroscience as we know it, with their discovery of the glymphatic system as the brain’s waste removal method (Hablitz and Nedergaard, 2021; Plog and Nedergaard, 2018) and the elucidation of the function of glial cells (Holst et al., 2019). In fact, Mollgard first suggested that an mesothelial barrier that lines other vital organs and systems must also exist within the CNS – a fact that was only recently proven through their study.

This study focuses on the passage of cerebrospinal fluid and the membranes surrounding the brain, traditionally thought to be the meningeal connective tissue layer. This was thought to comprise of an external tough outer layer called the dura mater (latin for “hard mother of the brain”), followed by an internal thin, well vascularised and tightly attached layer called the pia mater and the arachnoid mater, a web-like structure within the cerebrospinal fluid that connects to the pia mater. The cerebrospinal fluid is a transparent, colourless fluid that maintains homeostasis within the CNS, containing an aqueous solution of neurotransmitters, proteins and glucose (Wichmann et al., 2022). It cushions the CNS and was thought to be produced by the choroid plexus and absorbed in the subarachnoid spaces, however exact details were yet to be explained.

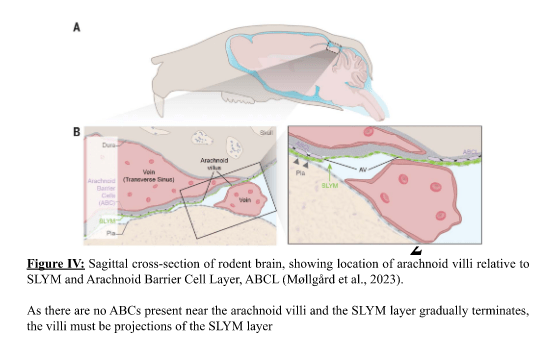

Mollgard and Nedergaard’s study illustrates however that a 4th layer exists below the arachnoid mater in the subarachnoid space, called the Subarachnoid Lymphatic-like Membrane (SLYM), serving as a bifurcation of this space. SLYM was named as such because it was found directly in the subarachnoid space, being lymphatic-like because it drains excess CSF just as lymphatic vessels normally would.

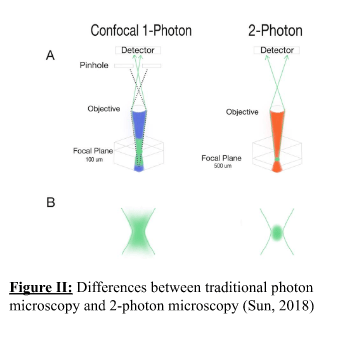

This discovery was achieved through two-photon electron microscopy, an expensive but powerful fluorescent imaging technique that utilises very fast 80 MHz laser pulses to fire two photons on biological tissue within 1 femtosecond (Lévêque-Fort and Georges, 2005). This technique provides high specificity for visualising tissue at a greater depth whilst maintaining high contrast, resolution and reducing issues of scattering, phototoxicity and photobleaching (Helmchen and Denk, 2005; Benninger and Piston, 2013), seen in Figure II.

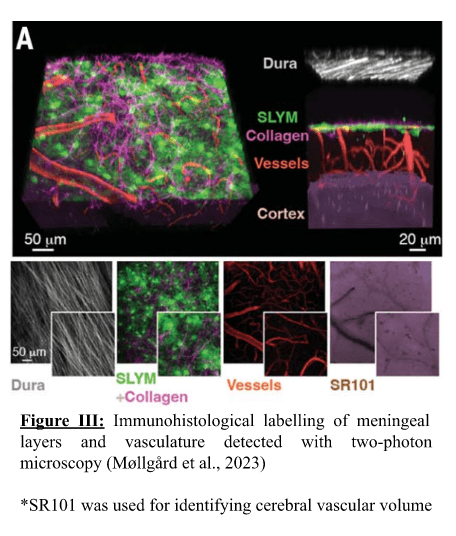

In the study, Prox1, a transcription factor relevant in lymphatic system formation, was fluorescently labelled in the dura mater and astrocytes, and two-photon electron microscopy was then applied. This helped them discover a loosely packed layer of collagen bundles and Prox1 cells that sub-divided the arachnoid space into an outer superficial section and an inner deep section that became the SLYM layer. Further testing with this technique demonstrated that it acts as an ultrafilter, separating clean and dirty CSF fluid by filtering against fine solutes (> 3kDa molecular weight) such as cytokines, growth factors and other peptides such as amyloid beta and tau, implicated in Alzheimer’s Disease. Fluorescence labelling showed that it possessed many lymphatic markers, some of which were not expressed in the pia/dura mater, and expressed PDPN, a common marker found in mesothelial cells and hence its classification as a mesothelial, lymphatic-like layer. This labelling also showed it lined the entire brain from front to back whilst possessing significantly different vasculature to the other meningeal layers that is populated by leukocytes. All of the above clearly indicates that it is a distinct mesothelial layer from the pia, dura and arachnoid maters, seen in Figure III.

In addition to this, it was found to form arachnoid villi lining the subarachnoid space and acting as a one-way valve that prevents the backflow of CSF. As a result, it is implied that the SLYM’s function is not only to filter CSF solutes and direct the flow of CSF into arterioles in the outer subarachnoid space, but also in CNS immune response.

While this study was conducted primarily on mice brains, it was also demonstrated to exist within human brains. What made this study a significant finding was not only the fact that human brains possessed a mesothelial layer as immunological defence for the CNS, but also that it may have a substantial role in diseases such as Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s, Dementia and Schizophrenia – all of which have been related to disorders in the passage of CSF via the glymphatic system (Zhang et al., 2022). The filtration system of the SLYM layer for CSF solutes accentuates the need for better low molecular weight treatment if given through spinal fluid intrathecally, as this can impair the effectiveness of such biologics(Soderquist and Mahoney, 2010). Interestingly, when this layer was damaged and CSF leakage occurred, two-photon electron microscopy detected these solutes on both sides of SLYM, which may perhaps explain the process of ageing and the progression of neurodegenerative diseases. Furthermore, treating the mice brains with LPS to stimulate bacterial infection as well as sampling older brains revealed a considerable surge in the variety and number of immune cells present, potentially explaining the correlation between ageing and reduced/impaired CSF distribution, in turn leading to neurodegenerative diseases (Zhang et al., 2022). SLYM layer damage may allow for hypersensitivity reactions to take place, as immune cells from the SLYM layer may attack the inner subarachnoid space and thereby the brain directly, consequently leading to prolonged neuroinflammation post traumatic brain injury and greater risk of neurodegenerative diseases. Given that some neurological diseases are postulated to be auto-immune in nature such as multiple sclerosis (Wootla et al., 2012; Barkhane et al., 2022), the SLYM layer may promote the progression of such diseases as lymphatic-like tissue can easily become hypersensitive when inflamed by viral infections, molecular mimicry etc. In fact, this discovery may even explain why sleep produces many neuroprotective effects for the brain, given that the glymphatic system is primarily active during restful REM sleep and in mostly inactive during wakefulness (Jessen et al., 2015), and that poor sleep has been correlated with impaired CSF circulation and hence amyloid-beta plaque accumulation (Sprecher et al., 2017).

Even though more research is required in understanding the specific mechanisms in which SLYM can get damaged and how this leads to neurodegenerative disease, this provides a solid ground for gaining a better understanding and appreciation for the role of cerebrospinal fluid and the glymphatic system in maintaining our brain.

References:

Barkhane, Z., Elmadi, J., Satish Kumar, L., Pugalenthi, L.S., Ahmad, M. and Reddy, S. 2022. Multiple Sclerosis and Autoimmunity: A Veiled Relationship. Cureus. 14(4), p.e24294.

Batista-García-Ramó, K. and Fernández-Verdecia, C.I. 2018. What We Know About the Brain Structure–Function Relationship. Behavioral Sciences. 8(4), p.39.

Benninger, R.K.P. and Piston, D.W. 2013. Two-Photon Excitation Microscopy for the Study of Living Cells and Tissues. Current protocols in cell biology / editorial board, Juan S. Bonifacino … [et al.]. 0 4, Unit-4.1124.

Hablitz, L.M. and Nedergaard, M. 2021. The Glymphatic System: A Novel Component of Fundamental Neurobiology. The Journal of Neuroscience. 41(37), pp.7698–7711.

Helmchen, F. and Denk, W. 2005. Deep tissue two-photon microscopy. Nature Methods. 2(12), pp.932–940.

Holst, C.B., Brøchner, C.B., Vitting‐Seerup, K. and Møllgård, K. 2019. Astrogliogenesis in human fetal brain: complex spatiotemporal immunoreactivity patterns of GFAP, S100, AQP4 and YKL‐40. Journal of Anatomy. 235(3), pp.590–615.

Jessen, N.A., Munk, A.S.F., Lundgaard, I. and Nedergaard, M. 2015. The Glymphatic System – A Beginner’s Guide. Neurochemical research. 40(12), pp.2583–2599.

Lévêque-Fort, S. and Georges, P. 2005. MICROSCOPY | Nonlinear Microscopy In: Encyclopedia of Modern Optics [Online]. Elsevier, pp.92–103. [Accessed 29 January 2023]. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/B0123693950008290.

Lisman, J. 2015. The challenge of understanding the brain: where we stand in 2015. Neuron. 86(4), pp.864–882.

Michaud, M. 2023. Newly Discovered Anatomy Shields and Monitors Brain. URMC Newsroom. [Online]. [Accessed 29 January 2023]. Available from: https://www.urmc.rochester.edu/news/story/newly-discovered-anatomy-shields-and-monitors-brain.

Møllgård, K., Beinlich, F.R.M., Kusk, P., Miyakoshi, L.M., Delle, C., Plá, V., Hauglund, N.L., Esmail, T., Rasmussen, M.K., Gomolka, R.S., Mori, Y. and Nedergaard, M. 2023. A mesothelium divides the subarachnoid space into functional compartments. Science. 379(6627), pp.84–88.

Plog, B.A. and Nedergaard, M. 2018. The glymphatic system in CNS health and disease: past, present and future. Annual review of pathology. 13, pp.379–394.

Soderquist, R.G. and Mahoney, M.J. 2010. Central nervous system delivery of large molecules: challenges and new frontiers for intrathecally administered therapeutics. Expert opinion on drug delivery. 7(3), pp.285–293.

Sprecher, K.E., Koscik, R.L., Carlsson, C.M., Zetterberg, H., Blennow, K., Okonkwo, O.C., Sager, M.A., Asthana, S., Johnson, S.C., Benca, R.M. and Bendlin, B.B. 2017. Poor sleep is associated with CSF biomarkers of amyloid pathology in cognitively normal adults. Neurology. 89(5), pp.445–453.

Sun, V. 2018. Dissecting Two-Photon Microscopy. Signal to Noise. [Online]. [Accessed 29 January 2023]. Available from: http://www.signaltonoisemag.com/allarticles/2018/9/17/dissecting-two-photon-microscopy.

Wichmann, T.O., Damkier, H.H. and Pedersen, M. 2022. A Brief Overview of the Cerebrospinal Fluid System and Its Implications for Brain and Spinal Cord Diseases. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience. 15, p.737217.

Wootla, B., Eriguchi, M. and Rodriguez, M. 2012. Is Multiple Sclerosis an Autoimmune Disease? Autoimmune Diseases. 2012, p.969657.

Zhang, D., Li, X. and Li, B. 2022. Glymphatic System Dysfunction in Central Nervous System Diseases and Mood Disorders. Frontiers in Aging Neuroscience. 14.

Leave a comment